8 Things You Don’t Know Are Affecting Our Choices Every Day: The Science of Decision Making

Making decisions is something we do every day, so I wanted to find out more about how this process works and what affects the choices we make. It turns out, there are some really interesting ways our decisions are affected that I never would have guessed. Luckily, we can take action to improve most of these.

What happens in your brain when you make decisions

Obviously lots of things take place inside your brain as you make a decision. What I found really interesting were the various things that affect our brain’s decision-making process without us ever realizing.

Why we accept the default choice

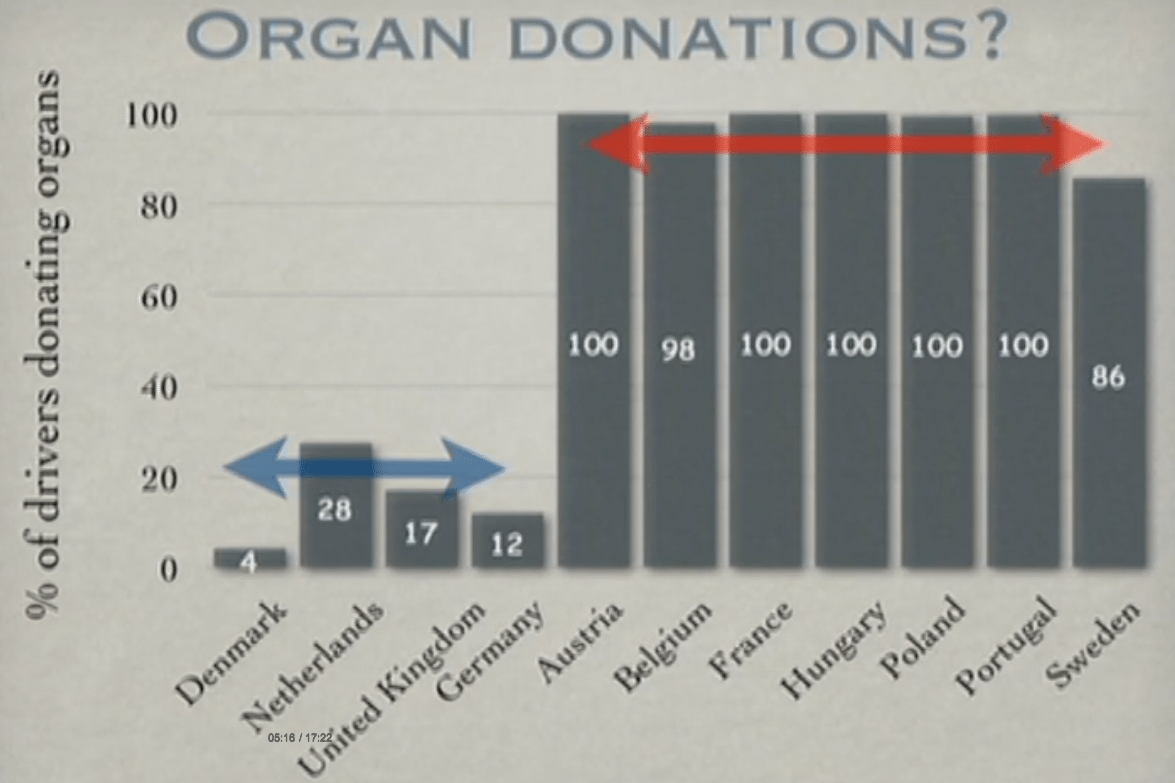

Dan Ariely’s excellent TED talk explains this concept really well with the example of organ donor options on driver’s license forms:

The overwhelming majority of drivers in the UK and European countries didn’t not check the box on their driver’s license application form.

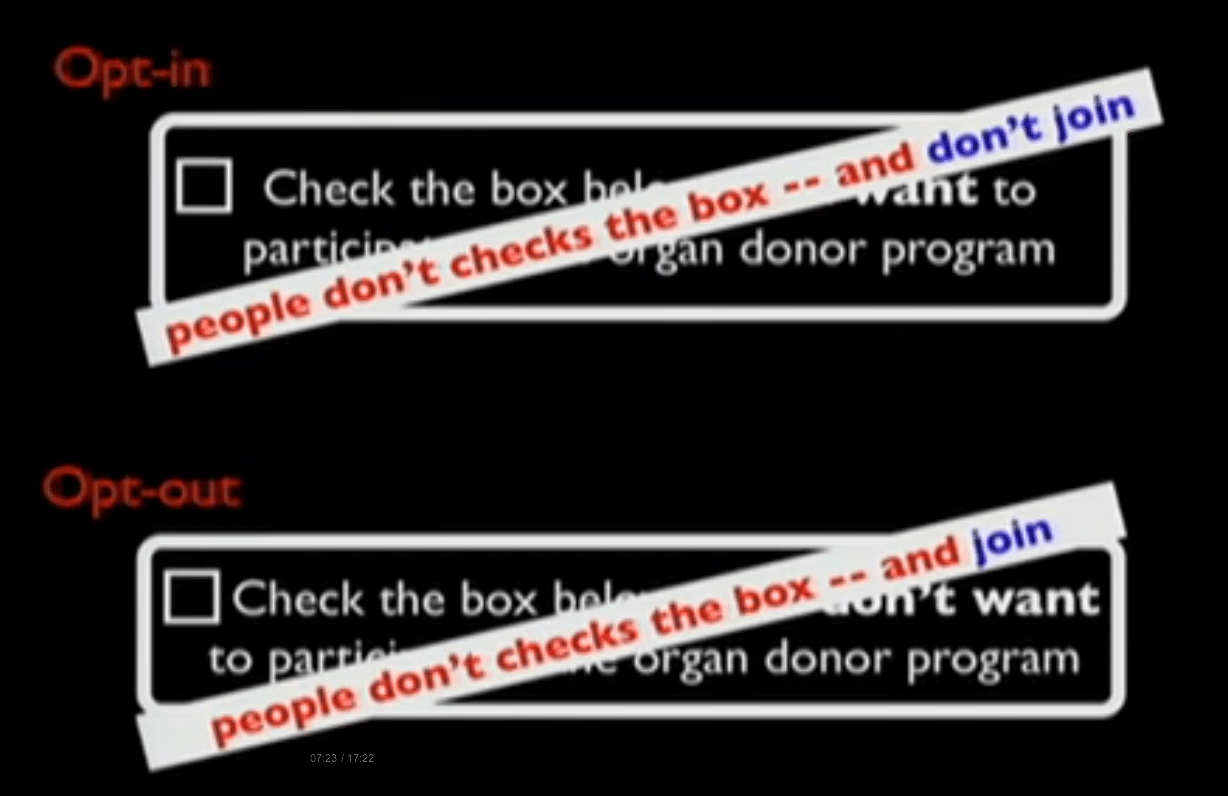

The funny thing is, in some countries, the box was an opt-in option, so people had to check the box to become an organ donor. In other countries, the form used opt-out, which means the box had to be checked to not be an organ donor. And still no one checked the box. So it was all down to the design of the forms:

If you watch the video all the way through, there are lots more examples of how this works in our brains. The problem is that deciding is too much effort. We’d rather not decide, so we’re likely to just stick with the default option if it’s already been chosen for us.

When we get offered too many choices, the same thing happens—we shut down, unable to decide. Often, we end up simply choosing anything, just to get the process over and done with.

Shai Danzinger’s study on parole hearings (which I reference in the next section) sums it up like this:

We start suffering from “choice overload” and we start opting for the easiest choice. For example, shoppers who have already made several decisions are more likely to go for the default offer, whether they’re buying a suit or a car.

Why we make worse decisions over time

Brian Bailey wrote about decision fatigue in an earlier post, which is essentially just a wearing-down of our decision-making abilities from overuse in a short period of time. The more decisions we make, the more tired our brain gets, leading us to either give less thought to our decisions or choose lower-risk, “safe” options simply to avoid the effort of making a difficult decision.

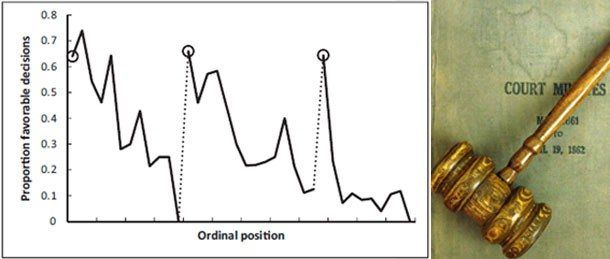

For a judge hearing a parole case, that safer, low-risk option would be to deny parole and keep the prisoner behind bars. Unsurprisingly, this is just what judges generally do when they’ve had to make a lot of decisions in a row.

A 2010 study found that judges were more likely to award parole early in the morning and immediately after taking breaks. As their string of cases grew longer and longer leading up to a break, the chances of a prisoner being awarded parole diminished substantially. Here is a terrific graph describing this how chances of favorable decisions are going down:

The study showed the following results:

… prisoners will be successfully paroled start off fairly high at around 65% and quickly plummet to nothing over a few hours… After the judges have returned from their breaks, the odds abruptly climb back up to 65%, before resuming their downward slide. A prisoner’s fate could hinge upon the point in the day when their case is heard.

The research was done by Shai Danziger from Ben Gurion University of the Negev, and examined the results of 1,112 parole board hearings in Israeli prisons over a ten-month period. The influence of the time since each judge had had a break was significant on the types of decisions they would make:

Danziger found that the three prisoners seen at the start of each “session” were more likely to be paroled than the three who are seen at the end. That’s true regardless of the length of their sentence, or whether they had been incarcerated before.

So the decision-making part of our brain works kind of like our physical muscles—the more we work it, the more tired it gets until we finally give it a break to recover and start over.

Why we make better decisions in the morning

Even the time of day affects our brain’s decision-making process. According to this excellent video by Baba Shiv, we should make more of our decisions in the morning. This is when serotonin is at it’s natural high, which helps to calm our brain. Shiv says this is a good thing because we feel less risk averse in the morning due to the serotonin in our brains, so we can take risks and make harder choices early in the morning.

Later in the day, serotonin starts to decline and we fall into a phase where we don’t want to make decisions at all. During the afternoon, Shiv says it’s common to postpone decisions because we favor indecision, or just avoiding making a choice at all.

Dr Amantha Imber, an organizational psychologist, recommends scheduling major decisions to be made before around 11 am, whenever possible:

Where decisions must be made at later times, taking a break without making any choices at all is recommended because ‘decision fatigue’ is difficult to fix without giving the brain a proper rest. If you know you are going to be making an important decision at say 4 pm, schedule some rest period immediately before that time.

Why we make better decisions in a foreign language

This one actually makes a lot of sense, but it surprised me at first. For those of us who learn a foreign language as adults (as opposed to being raised bilingual), the emotional effects of that foreign language don’t resonate with us the way our native language does. For instance, curses don’t give us the same relief or sense of shame in a foreign language as they do in our mother tongue.

This is due to something called ‘framing effects’:

When a decision is verbally framed as involving a gain, humans prefer a sure outcome over a probabilistic outcome. When the same situation is framed as involving losses, people sometimes prefer to gamble. For example, given a scenario involving 600 sick individuals and two types of medicines to administer, research participants prefer the medicine which will save 200 people for sure, rather than the medicine which has a 1/3 chance of saving all 600 sick people and a 2/3 chance of saving no one. If the formally identical illness scenario is provided, but framed in terms of how many people will die, then research participants are more likely to choose the probabilistic option.

Experiments with foreign-language decision-making found that framing effects don’t work the same way when we use a different language to frame a situation:

The Chicago researchers randomly assigned bilinguals to read and respond to decision-making scenarios using either their native or foreign language. Similar versions of the study were conducted in the U. S, France and Korea. Data from all three locations were consistent: the standard framing effects were found for the native language and were absent in the foreign language. The implication is that people were less influenced by emotional aspects of the scenarios when reading scenarios in their foreign language.

This can actually be beneficial when it comes to making decisions, because we’re less likely to fall prey to emotion-based marketing or making irrational decisions if we use a foreign language.

How our bodies play a part in our decision-making

I would have thought our brains had the biggest role in how we make decisions but I was surprised to realize that our bodies also play a big part.

Why being hungry is bad for decision-making

One of the funny things about how our bodies work is that sometimes feelings or states of being can spill over from one area to another. Our physical desires work like this. If we’re feeling hunger, thirst or sexual desire, for instance, that can actually spill over into the decision areas of our brains, making us feel more desire for big rewards when we make choices. This can lead us to make higher-risk choices and to want for more, as explained in this Brain Study article:

Fasted individuals also make riskier bets on a financial decision-making task involving lottery choices, opting for the riskier option significantly more often when fasted, and choosing the safer bet when full. This finding is supported by the animal literature, in which animals are more risk-averse when sated but risk-seeking when hungry. This is presumably an evolutionarily selected trait prompting exploration and risk-seeking when in states of hunger, which could potentially lead to the acquisition of new food sources.

Why a full bladder helps us make better choices

Just like feelings of desire can spill over to the choices we make, so can our self-control. Mirjam Tuk, of the University of Twente in the Netherlands, knew about the research into how our desires affect our choices and wanted to see how self-control, or inhibition of desires, might affect us.

In one experiment, participants either drank five cups of water (about 750 milliliters), or took small sips of water from five separate cups. Then, after about 40 minutes – the amount of time it takes for water to reach the bladder – the researchers assessed participants’ self-control. Participants were asked to make eight choices; each was between receiving a small, but immediate, reward and a larger, but delayed, reward. For example, they could choose to receive either $16 tomorrow or $30 in 35 days.

The researchers found that the people with full bladders were better at holding out for the larger reward later. Other experiments reinforced this link; for example, in one, just thinking about words related to urination triggered the same effect.

It turns out, having a full bladder and therefore inhibiting the desire to empty it spills over to our self-control when it comes to making decisions. We’re more likely to choose low-risk options and to avoid impulse decisions when we’re controlling ourselves physically.

Why ventilation is important for good decision-making

We know that air pollution is bad, and you’ve probably heard about how having plants in the office is good for productivity and general wellness. It turns out, plants and good ventilation are more important than we might have realized.

A study of CO2 levels in a working space found that as CO2 is increased, even when it’s still below the recommended safe levels, our cognitive ability decrease. The higher the CO2 in the room, the more sharply our mental abilities decline.

The work assessed decision-making in 22 healthy young adults. Their performance on six of nine tests dropped notably when researchers raised indoor carbon dioxide levels to 1,000 parts per million from a baseline of 600 ppm. On seven tests, performance fell substantially more when the room’s CO2 was boosted to 2,500 ppm

The researchers suggested adequate ventilation to decrease CO2 levels, particularly in rooms with lots of people, like big offices or classrooms.

Why leaning to the left affects your choices

Did you know we store numbers in different parts of our brains depending on how big the numbers are? We actually store bigger numbers on the right and smaller numbers on the left. The strange thing is, leaning our body towards one side or the other can influence our decisions when we’re trying to estimate numbers.

An experiment at Erasmus University Rotterdam in the Netherlands that tested this had participants stand on a Wii board while answering questions. Although the screen told participants their posture was straight the whole time, some of them were made to lean slightly to one side by the board they were standing on. The researchers didn’t notice any significant differences when participants leaned right or stood up straight, but when they leaned left, they more often chose smaller estimates than otherwise.

The researchers stressed that leaning won’t make you answer incorrectly or override any actual knowledge you have, but simply inform your decisions somewhat. I love the way one of the scientists involved, Rolf Zwaan explained this:

Decision-making is not a pristine process. All sources of information creep into it, and we are just beginning to explore the role of the body in this.

How to make better decisions

Since we have all of this information, let’s see how we can put it to use and make better decisions.

1. Make your decisions in the morning

With a combination of serotonin and dopamine levels, and no decision fatigue to get you down, the morning is the best time to make big decisions. If you do have to make big decisions in the afternoon, you could try taking a nap or just a relaxing break to reset your brain first.

2. Eat first

We know all about not doing the grocery shopping on an empty stomach, right? Well it seems like we don’t want to make any decisions when we’re hungry if we can avoid it. Try to keep your physical desires taken care of before meetings or phone calls when you’ll be called on to make some big choices.

3. Cut down your choices

We often settle for default options or let others decide for us because decisions are just too much work for our brains. This is particularly so when there are more than two options to choose from. You can help your brain out by cutting out any extra options you don’t need. Cut your choices right down to a tiny shortlist and you’ll have an easier time of making a final decision.

4. Open the windows

Keeping the CO2 levels low in your home or workspace is really important for all cognitive functions, not just decision-making. Adding plants will certainly help, but try to keep fresh air circulating as well, particularly in high-traffic areas where lots of people are around, contributing to the CO2 levels.

5. Use a foreign language

If you know one, this could be really useful. Particularly when there are lots of emotions involved, or you want to protect yourself against things like emotional marketing strategies. Try explaining the situation to yourself and replying with your decision in a foreign language and see how differently you process that information.

This article first appeared on the Buffer Social blog in July 2013 and has since been moved here to the Open blog.

Try Buffer for free

140,000+ small businesses like yours use Buffer to build their brand on social media every month

Get started nowRelated Articles

As a self-proclaimed tools nerd, I’ve tested out many of the ever-growing list of AI productivity tools on the market. These are the ones I keep coming back to.

Looking for some low-lift ways to make yourself happier? Here's some of the best research that we've found on personal happiness.

Personal brand experts walked this writer through exactly how to switch up her personal brand — and offered some more general advice, too.