The 6 Exercises We’re Doing to Help With Artificial Harmony

Chief of Staff @ Buffer

Have you ever walked out of a meeting and messaged someone who had been in that very meeting to say something that you didn’t feel you could say in front of the group?

I know I have.

A while back, we came across the concept of “Artificial Harmony” which is one way to describe that feeling I just mentioned.

In Patrick M. Lencioni’s The 5 Dysfunctions of a Team, Artificial Harmony refers to a team of people who don’t have very much “healthy conflict,” which he defines as “passionate, unfiltered debate around issues of importance to the team.” In fact, not only do those teams not have healthy conflict, but they generally don’t have much conflict at all.

However, this lack of conflict isn’t necessarily a sign of a like-minded, fully-aligned group with a project that is humming along smoothly. On the contrary, it usually means that essential conflict isn’t happening, resulting in disengaged team members and the rare, honest conversations happening in the shadows.

After learning this, we started paying attention.

Artificial Harmony and the Pyramid of Dysfunction

In Lencioni’s theory, the fear of conflict (Artificial Harmony) is one of five interrelated steps within a pyramid:

Source: Abinoda

An absence of trust within teams leads to a fear of conflict.

This fear, in turn, causes a lack of commitment from team members because they haven’t openly expressed their objections.

The lack of commitment reduces accountability in the team and ultimately has a detrimental effect on results.

Overcoming these challenges may be one of the most effective ways to achieve very strong results as a team.

Each of these five dysfunctions has its own signals and warning signs. Some warning signs of Artificial Harmony, in particular, are the following:

- Boring meetings with little spirited discussion

- Individuals feeling hesitant to voice dissent during discussions, and leaving feeling unresolved

- Teammates resorting to back-channel conversations in order to raise concerns

- A lack of team-wide buy-in: internal hesitation and a quiet reluctance to commit to decisions.

What Artificial Harmony Looks Like at Buffer

The Buffer team works quite hard at being kind, even gentle, with each other. As a global team, we have several values specifically related to how we communicate. For example, we make an effort to listen before speaking, use extra words to avoid miscommunication, assume good intention, recognize our own missing context, and show gratitude for each other. All good things, right? These goals have helped us create a culture that reflects our values, and we hold those values dear.

However, when we came across Artificial Harmony, we realized that it sounded a bit like us.

We learned that, in pursuit of some of those values, we were depriving ourselves of healthy conflict.

For example, our value of “choosing positivity” has a point about withholding criticism from teammates and avoiding complaining. Similarly, we strive to “show gratitude” for our teammates, customers, and our situation. Because of those values, we often hesitate to voice struggles or critiques, lest they be seen as negative or damage the gratitude that our teammates felt for their hard work. It wasn’t until we kicked off a team-wide discussion about the nuances of our values that we felt comfortable with more honest, well-intentioned debate.

We’ve made several stops on our path toward understanding the causes and risks of Artificial Harmony and the reward of overcoming it. Here’s what we’re trying, and why.

6 Exercises You Can Try

Building Trust: Vulnerability in a team setting

Like most relationships, a foundation of trust is where to start. Without a safe environment where teammates can admit truths and avoid office politics, the rest of the pyramid doesn’t work.

Quote source: Overcoming the Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Field Guide for Leaders, Managers, and Facilitators

Exercise number 1: Personal Histories

What it is: In this exercise, teammates share some details about their lives that are non-sensitive but not always widely known. Some examples are previous jobs, hobbies, childhood memories, and families.

Why try this: This should help create a basic friendship and understanding in the team. It isn’t intended to be highly emotional, but a private and unhurried environment is great for this one.

Risks: This can backfire if teammates are not respectful of the information shared. I suggest establishing some understood or explicit norms for this activity.

How we do it: We try to keep this on a “slow burn,” but it’s especially key for us as a remote team. New teammates are encouraged to spend some time getting to know the human on the other side of that computer. We have a casual “pair call” system for teammates to chat with random teammates about their work and lives. In some smaller groups, we begin meetings with an icebreaker that contributes to our collective personal history knowledge. And, at our annual retreats, there are walks, meals, and late night conversations that help here, too.

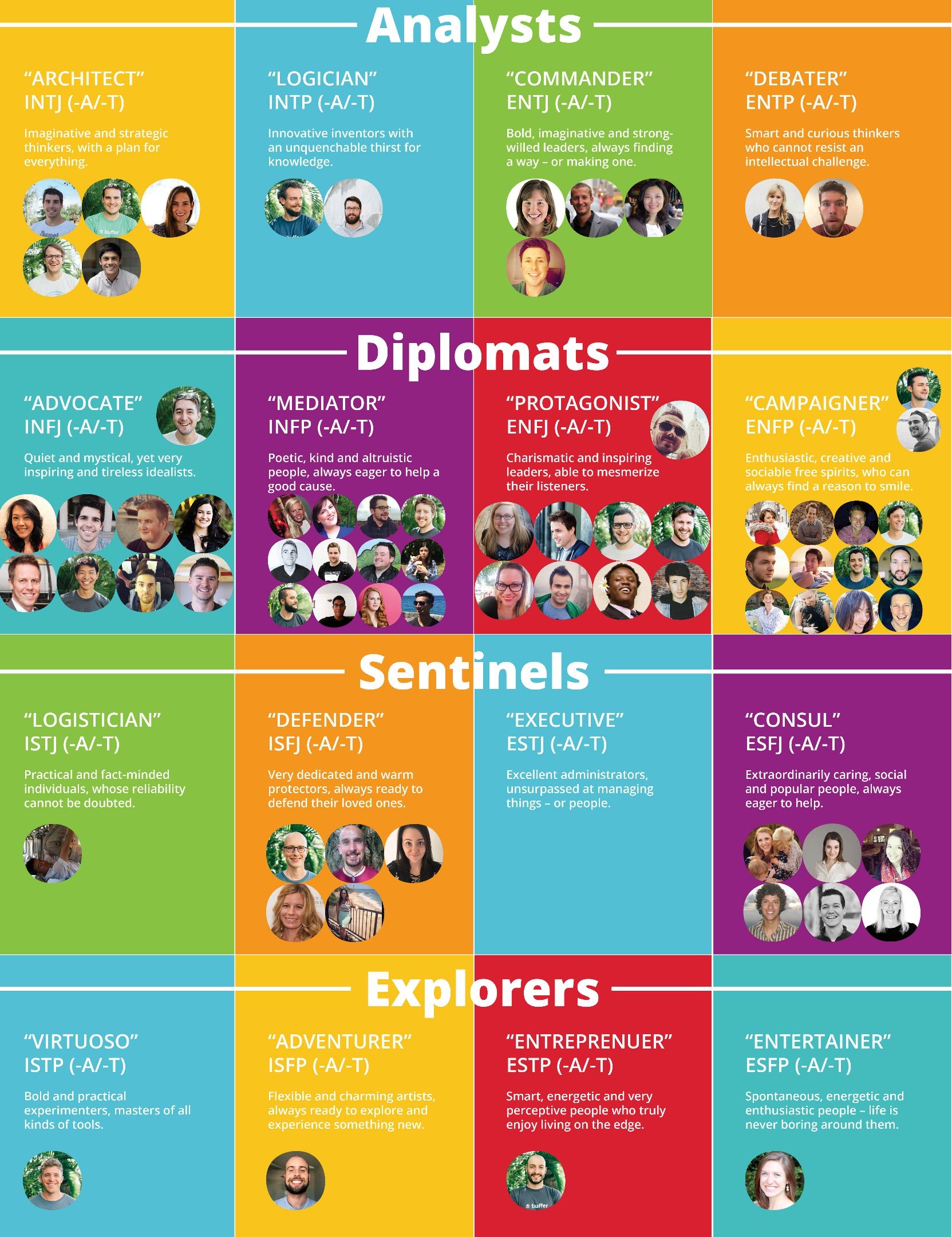

Exercise number 2: Behavior Profiling

What it is: In this exercise, the team uses a tool that relies on an established matrix of personality types, complete with strengths, fears, and preferences. Some well-known examples are Myers-Briggs, DiSC, and Strengths Finder.

Why try this: Personality profiles give teams an “objective, reliable [vocabulary] for understanding and describing [ourselves and] each other.” (Source: Overcoming the Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Field Guide for Leaders, Managers, and Facilitators)

Risks: Teammates may resent being put into “boxes,” and some resistance to certain oversimplifications can occur. I suggest making it clear that, while this is useful to help the team understand each other, it is a tool and should not be followed blindly.

How we do it: We each completed the test on 16personalities at our most recent retreat in Madrid. Then, we hung a large poster in a central location, and placed our avatars on the corresponding types. Our People Team then shared a digital document with each teammate’s personality type, and invited us to read the description for those we work closely with. We are invited to refer to our own personality types when it’s useful.

Mastering Conflict: Passionate, unfiltered debate.

The goal of healthy conflict is for team members to say everything that needs to be said, meaning nothing is left to be discussed behind closed doors.

Exercise number 3: Conflict Profiling

What it is: Similar to behavior profiling, this exercise invites each teammate to share their own personal habits and preferences in relation to conflict specifically. For example, some teammates much prefer to have disagreements or receive feedback over a written medium to allow for reflection and careful word choice. Others much prefer video conversations to observe body language and reduce the chances of an unrealized miscommunication.

Why try this: We often assume that others have the same tolerance and habits around conflict that we do. However, these can vary greatly according to personality, culture, and family habits. You can remove the risks of assuming by being explicit here.

Risks: The risks here are fairly low! However, it may uncover some differences in teammates’ preferences, which can cause friction.

How we do it: First, we have had several conversations as a team to normalize all conflict types, calling attention to the fact that teammates do have completely opposite reactions to certain things. We have also added a field to our slack profiles to indicate our preferences so a teammate can check it easily and respect it when possible.

Exercise number 4: Conflict Norming

What it is: In this exercise, you draw upon the team’s personalities and spoken preferences and create a “conflict constitution” of sorts. This is an agreed-upon set of norms and habits that are documented and regularly reviewed.

Why try this: This creates expectations for the team and allows each person to prepare for conflict accordingly. It can be referenced as often as necessary to reinforce the agreement.

Risks: Out of necessity, this may set some practices that don’t match everyone’s preferences perfectly. In this case, I suggest building in breaks for the less confrontational to rest and creating a separate, open space for the more confrontational to reach equilibrium.

How we do it: We have only recently piloted this one. Several of our Product and Engineering teams have created their own conflict constitution.

Exercise number 5: Mining for Conflict

What it is: One person takes on the role of gently unearthing buried conflict through intentional questioning. This may be the team lead, one elected teammate, or a rotating role.

Why try this: This exercise challenges artificial harmony most directly, encouraging team members to voice and address objections. If done effectively, this drastically reduces the likelihood of teammates leaving meetings without feeling the commitment to the conclusion.

Risks: This exercise illustrates the importance of the pyramid structure. Without a strong base of trust in a team, mining for conflict won’t work.

How we do it: Similarly, we have only begun to be explicit about this one. Certain teammates have unofficially taken on this role throughout history, but it has almost always been team leads. Now several teams have elected a teammate to serve in this role explicitly for the length of a project.

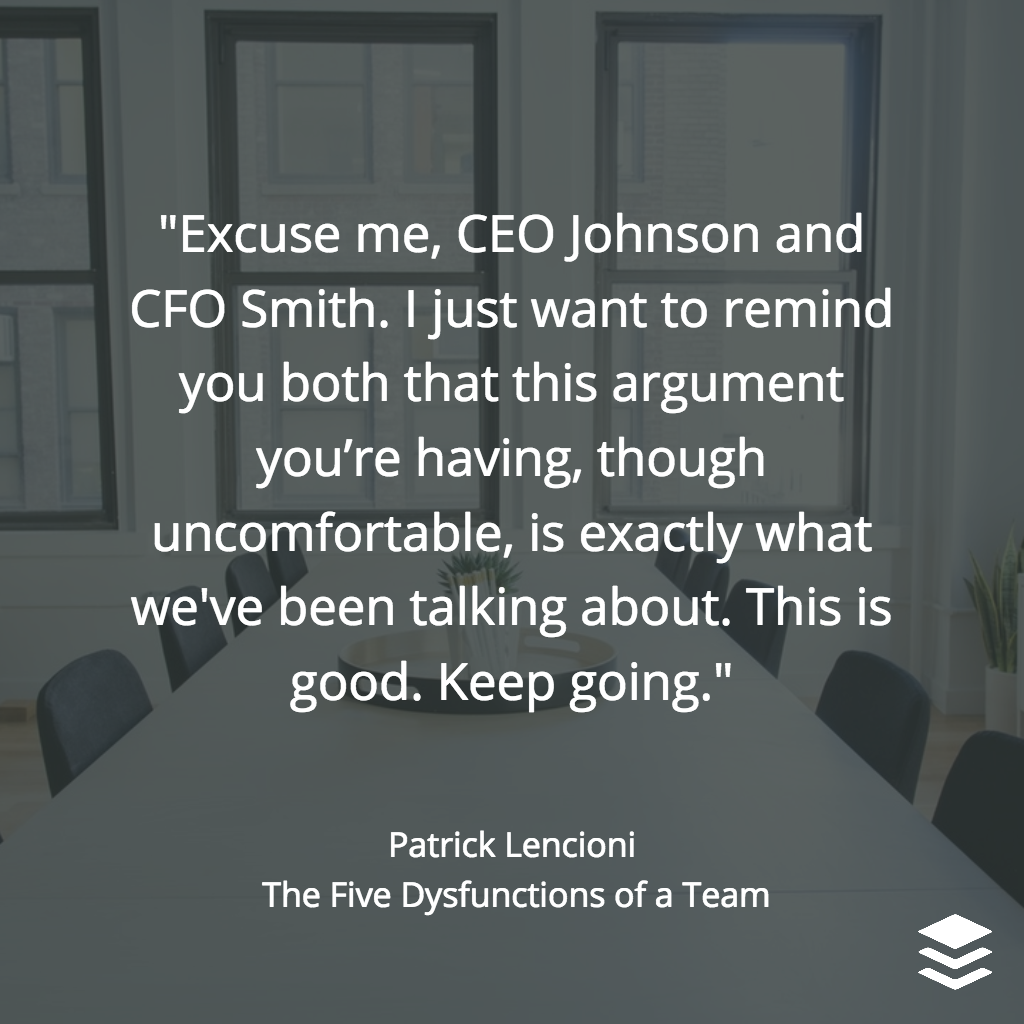

Exercise number 6: Real Time Permission

What it is: Anyone, especially a team lead or the elected teammate, regularly reminds everyone that healthy conflict is important, necessarily, and valuable, even though it is uncomfortable and hard. This person may even occasionally interrupt active conflict in order to make this point and give encouragement.

Why try this: These reminders can help teammates push through the awkwardness of active conflict. It helps remind everyone that we’re on the same team, and we voice dissent in order to reach the best conclusion for everyone.

Risks: If overused or poorly timed, it may derail the good conversation, so I suggest practicing this one in less heated conversations first, and learning to feel out when it seems like the reminder is needed.

How we do it: This is one of the exercises that I personally have found the most helpful over the years. In our executive meetings, we have unofficially traded off giving these reminders that we feel passionate about because we care about the results and growth of the whole team, and it serves to point out that our goals are aligned, even if our opinions may differ.

What’s next after healthy conflict?

While we have made some great progress on our journey toward team trust and healthy conflict, I don’t expect us to find ourselves done with these efforts anytime soon. It feels a bit like other relationships; trust and communication take regular investment.

However, as we’ve made progress on the healthy conflict side, we’ve been able to see higher levels of commitment to decisions, because teammates feel like their dissenting opinions have been considered. (We sometimes refer to this concept as the phrase Jeff Bezos’ popularized on this topic: “Disagree and Commit.”) This has led us to higher levels of accountability, and results have followed.

It’s exciting progress, and we still feel like we have plenty of room to grow on all of these fronts. Follow along with us on this (and all journeys), right here on the Open blog.

Over to you!

- Do some of these symptoms resonate with you?

- Have you tried any of these exercises?

- Have you read the five dysfunctions of a team book? If so, what did you think?

As always, we’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments or on Twitter! I’m @carokopp, and we’re @buffer. Thank you as always for your attention and conversation.

Try Buffer for free

140,000+ small businesses like yours use Buffer to build their brand on social media every month

Get started nowRelated Articles

In this article, the Buffer Content team shares exactly how and where we use AI in our work.

With so many years of being remote, we’ve experimented with communication a lot. One conversation that often comes up for remote companies is asynchronous (async) communication. Async just means that a discussion happens when it is convenient for participants. For example, if I record a Loom video for a teammate in another time zone, they can watch it when they’re online — this is async communication at its best. Some remote companies are async first. A few are even fully async with no live ca

Like many others, I read and reply to hundreds of emails every week and I have for years. And as with anything — some emails are so much better than others. Some emails truly stand out because the person took time to research, or they shared their request quickly. There are a lot of things that can take an email from good to great, and in this post, we’re going to get into them. What’s in this post: * The best tools for email * What to say instead of “Let me know if you have any questions” a